- What is Chanoki? Discover the Matcha Plant Where All Tea Begins

- All From One Tree! Green Tea, Matcha, and Oolong All Come From Chanoki

- It’s All in How They’re Grown: The Secrets Behind Matcha and Green Tea

- Sunlight is Key! How Shaded Cultivation Boosts Umami

- To Roll or Not to Roll? The Process That Defines the Tea

- From Tencha to Matcha: The Flavor Crafted by the Stone Mill

- How Sencha is Made: The Blessings of the Sun and the Skill of the Artisan

- A Brief History of Chanoki: Its Journey to Japan

- Japan’s Three Great Teas: Famous Tea-Growing Regions

- Try it at Home! How to Grow and Enjoy Your Own Chanoki

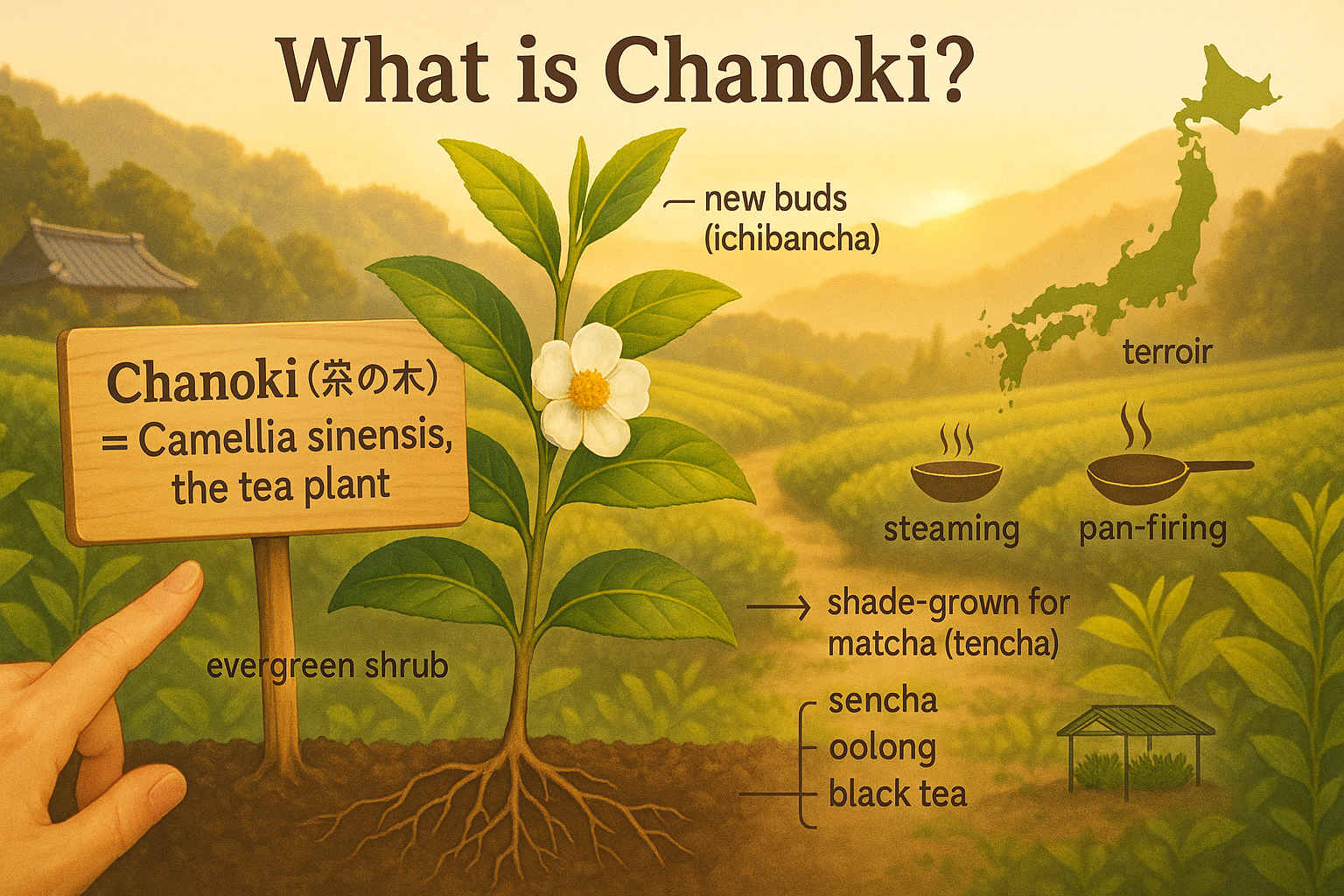

What is Chanoki? Discover the Matcha Plant Where All Tea Begins

Ever wonder about the green tea or matcha you enjoy every day? You might be surprised to learn they all come from just one type of plant! It’s called “Chanoki” (茶の木), or the tea plant. Its scientific name is Camellia sinensis, an evergreen tree from the same family as the beautiful camellia flower. As an evergreen, it keeps its glossy, deep green leaves all year round and blooms with lovely white flowers in the fall. The leaves of this single plant are the starting point for every tea in the world. It’s hard to believe when you look at the tea in your cup, but it’s true—the diverse world of tea all starts right here.

All From One Tree! Green Tea, Matcha, and Oolong All Come From Chanoki

It’s amazing how many different teas can be made from the Chanoki plant. Think of refreshing green tea, rich and savory matcha, floral oolong tea, and deep, reddish-black tea. They all start from the very same leaves. So, what makes their tastes, aromas, and colors so different? The secret is in how the leaves are processed after harvesting—specifically, how much they are “oxidized.” Green tea is an “unoxidized tea,” where the leaves are heated right away to stop the natural enzymes. Oolong tea is a “semi-oxidized tea,” where the process is allowed to happen for a little while. And when the leaves are fully oxidized, they become black tea. In this article, let’s focus on two teas that are beloved in Japan: green tea and matcha, and dive into their secrets.

It’s All in How They’re Grown: The Secrets Behind Matcha and Green Tea

Both matcha and other Japanese green teas are “unoxidized,” but their flavor and color couldn’t be more different. The first key difference happens long before the leaves are picked—it all comes down to the cultivation method. The biggest factor? Sunlight. Most green tea, like Sencha, comes from plants that are grown in full, direct sunlight. This is called “open-air cultivation” (Roten Saibai). In contrast, the leaves destined to become matcha are grown under shade for a period before the harvest. This special technique, almost like holding a parasol over the plants, is the first crucial step in creating matcha’s brilliant green color and smooth, mellow umami flavor.

Sunlight is Key! How Shaded Cultivation Boosts Umami

This special method of blocking sunlight to grow matcha is called “shaded cultivation” (Oishita Saibai). As new buds start to sprout, the entire tea garden is covered with reed screens, straw, or modern black nets. This cover blocks direct sunlight from reaching the leaves. Why is this so important? In sunlight, plants use photosynthesis to convert their savory “theanine” into astringent “catechin.” By limiting sunlight, this process is slowed way down. As a result, the leaves store up lots of the delicious umami component, theanine. To make up for the lack of light, the leaves also produce more chlorophyll, which makes their color a deeper, more vibrant green. This is the source of matcha’s signature low bitterness, rich umami, and beautiful color.

Note

Theanine: An amino acid that gives tea its signature umami and sweetness. It’s also known for promoting relaxation.

Catechin: A type of polyphenol that causes the astringent (or bitter) taste in tea. It has become famous for its many benefits.

To Roll or Not to Roll? The Process That Defines the Tea

What happens after the leaves are picked is the next key step that separates green tea and matcha. Freshly picked leaves begin to oxidize right away, so they are immediately steamed at a high temperature to stop the process. This first step is the same for both. After that, however, their paths diverge. For common green teas like Sencha, the leaves go through a “rolling” or kneading (Junen) process. This breaks down the leaf tissues, which helps release the flavor and aroma when you brew the tea. On the other hand, leaves that will become matcha are not rolled at all. After steaming, they are simply dried. This simple difference—to roll or not to roll—completely changes how the final tea looks and is enjoyed.

From Tencha to Matcha: The Flavor Crafted by the Stone Mill

Tea that is shade-grown, steamed, and dried without being rolled is called “Tencha.” This is the raw material for matcha. Tencha leaves are flat and flaky, a bit like nori (seaweed). To prepare them, workers carefully remove all the tough stems and veins, selecting only the softest parts of the leaf. This premium Tencha is then ground very slowly in a stone mill. This step is critical to the quality of the matcha. Using a high-speed machine would create friction heat and ruin the delicate flavor. By grinding slowly with a stone mill, very little heat is generated, preserving matcha’s unique aroma and umami. The result is the fine, silky, vibrant green powder we know as matcha. Because you consume the entire leaf as a powder, you also get all of the nutrients the Chanoki plant has to offer.

How Sencha is Made: The Blessings of the Sun and the Skill of the Artisan

Now for Sencha, one of the most popular green teas in Japan. It’s made from Chanoki leaves that have soaked up plenty of sunshine. Just like with Tencha, the leaves are steamed immediately after harvesting to stop oxidation. The length of this steaming process can be varied to create different types, like light-steamed or deep-steamed, each with its own flavor profile. After steaming, the leaves are rolled and dried. This rolling process does more than just dry the leaves; it helps the flavorful components dissolve easily in hot water, bringing out the tea’s wonderful taste and aroma. Skilled artisans carefully adjust the rolling time and pressure based on the day’s weather and the condition of the leaves. Through this process, Sencha is shaped into its beautiful, needle-like form, full of refreshing bitterness from sun-ripened catechins.

A Brief History of Chanoki: Its Journey to Japan

Tea has an ancient history that began in China. The Chanoki plant was first widely introduced to Japan in the early Kamakura period (around the 12th century). The story goes that Eisai, a Buddhist monk, brought back tea seeds from his studies in China. He even wrote a book called the “Kissa Yojoki” (“Drinking Tea”), promoting tea for its benefits. At first, tea was used by monks to stay awake during Zen meditation and was considered a luxury among nobles and samurai. Later, as the tea ceremony culture blossomed, Chanoki cultivation spread across Japan, and the custom of drinking tea became a beloved part of daily life for everyone.

Japan’s Three Great Teas: Famous Tea-Growing Regions

Japan is home to many regions perfect for growing tea. Among them, three are especially famous and are known as the “Three Great Teas of Japan.” First is Shizuoka Tea, which produces the most tea in Japan. Its warm climate and sunny days are ideal for growing a wide variety of teas, especially Sencha. Second is Uji Tea from Kyoto, a region proud of its long history and tradition. It’s famous for high-end matcha and gyokuro made using shaded cultivation. Third is Sayama Tea from Saitama Prefecture. It’s known for its distinct, rich flavor, praised in a classic song: “Color from Shizuoka, aroma from Uji, and taste from Sayama.” Beyond these three, unique teas are grown all over the country, from Yame in Fukuoka to Chiran in Kagoshima, each offering a different flavor shaped by its local climate and soil.

Try it at Home! How to Grow and Enjoy Your Own Chanoki

Did you know you can grow a Chanoki plant at home? You can often buy a garden seedling and grow it in a pot or your yard. As a member of the camellia family, it’s a hardy plant and fairly easy to care for. It loves a sunny spot with good drainage and will sprout new buds in the spring and fall. You can even try making your own simple tea by picking the fresh leaves! For a homemade pan-fired tea, just lightly pan-fry the leaves, roll them by hand, and let them dry. While it may not taste like a professionally crafted tea, the experience of brewing a cup from a plant you grew yourself is truly special. Growing your own Chanoki can give you a deeper appreciation for your daily cup of tea, making it feel even more precious and flavorful.